Anyone who knows me knows I am infatuated with Jimmy Carrane. I ardently recommend his podcast to anyone who will listen and just about lost it when I learned he was visiting us here. I can say with only mild shame that I was starstruck when I met him. Fortunately, that was quick to pass when the workshops began as there was notime to reflect, we had improv to get to

Now that a few weeks have passed since the workshops completed, I wanted to relate my thoughts on his visit and some of the  discoveries I’ve made with his help. Jimmy’s teaching focuses heavily on being real. We’ve all heard and repeated “Get out of your head!” ad nausem but Jimmy actively forces improvisers to escape the confines of their mind and to be in the scenes. This left virtually no time for notes, so to help reflect, I’ve selected some quotes from my latest reading of his excellent book Improvising Better: A Guide for the Working Improviser and used those as jumping off points.

discoveries I’ve made with his help. Jimmy’s teaching focuses heavily on being real. We’ve all heard and repeated “Get out of your head!” ad nausem but Jimmy actively forces improvisers to escape the confines of their mind and to be in the scenes. This left virtually no time for notes, so to help reflect, I’ve selected some quotes from my latest reading of his excellent book Improvising Better: A Guide for the Working Improviser and used those as jumping off points.

To begin, we must escape the explicit thought process and stop trying to control.

“These improvisers . . . cherry-pick, becoming selective on what to say yes to, thinking they can predict which idea will be the most successful.”

I am guilty of this – trying to control the flow of a scene. In his workshop, Jimmy admonished me for not accepting my partner’s gifts with a simple yes. This manifested itsel

f not in outright denials but in an attempt to keep the scene in a stable reality where no one is the bad guy. I was not letting myself play the absurd. I was not losing myself in the moment. For example, when told “You’ve been cheating on me,” I would reply with something like “I know, but we haven’t loved each other for a long time.” This is subtledisagreement. Sure, it moves a plot, but it needlessly creates conflict that is going to make it difficult to avoid an argument.

To break this, we did an exercise. A line of players marched up to me one at a time and accused me of some social error, such as “You’re a cheater” or “Your personality is terrible.” My job was to explicitly accept this gift and then justify it – e.g. “You’re right that I’m terrible because I always eat pickles in bed.” The exercise was eye-opening to see that agreement works so simply and so well, yet it requires blind acceptance. With that comes beautiful discovery and rich scenes.

I recently saw a short-form show where the troupe asked for very good suggestions (What item would you like to have on a island? Where are you likely to find Hilary Clinton?). They received strong input from the audience for these. Unfortunately, they waited for the “right” one. They would look from player to player repeating the words they heard and then, after 5 or 6, nod vigorously and say “Yeah, that one, let’s do Cartwheel.” They did this for every game. While they were strong performers and the scenes were great, it was disappointing to watch the wheels turn and see them select ideas instead of running with the suggestion.

A caveat is that this was a somewhat rowdy crowd, so the normal dismal suggestions of gynecologist and dildo were rampant. They tried to stymy this with a powerpoint that forewarned this (“You might think these are funny suggestions, but they are not. Please refrain from the following: [list]”). Regrettably, this warning came during intermission and was far to late to be effective. And with a transient, rowdy crowd, the preferred strategy of taking the blue suggestion and playing it smart is much more difficult. However, it would have been refreshing to see the group take suggestions that they were not expecting or that they did not have time to mull over before selecting. Presumably, then they would be discovering along with us.

“The beauty of this work is the element of surprise to your partner, to the audience, and to yourself.”

This same tendency to control can be attributed to a lack of commitment. Commitment is a player’s willingness to make a choice and stick with it. No one wants to watch (let alone play in!) a scene where we don’t know what we’re doing, what object we’re holding, what emotion we’re exploring, or anything else. Vagueness is boring, and boring is bad.

Commitment relieves us of this boredom. Once we overcome the fear and unwillingness of naming the specifics, our partners and audiences will be happier. Why? We’ve just relieved them of the burden of doing so! An example from Jimmy’s book:

Daughter: You hit me.

Father: I’m sorry I did that.

That is a boring scene. What happens if we add a couple specifics?

Daughter: You hit me, you bastard.

Father: I did, and I’ll do it again if I catch you sleeping with that Parker boy.

Much better. And as Jimmy points out, playing the Parker boy is now a viable option that will certainly lead to great discoveries later in the form!

What other specifics could we offer in there? Since we want to keep the underlying agreement (i.e. a father just hit his daughter), we can’t downplay it and deny the accusation. So, responses like “It was just a tap” or “I didn’t mean to” or even “Don’t tell anyone” aren’t going to be the best. Rather, we’d like to accept that the father is a bad person who’s done something bad. Some potential responses would be “You’re growing up, it’s time you learned how this family runs,” or “You’re right, and I’ve wanted to do that for so long,” or even “Yes, and now I’m calling the police.” Notice that the father does not get off the hook in any of the responses – after all, he’s the bad guy! By accepting that, we’re about to see a scene that is emotionally charged, has flawed characters, and is likely to lead to unexpected discoveries. While it may be ugly, that’s exactly what makes it entertaining.

These realizations came quickly in Jimmy’s workshops. Often the players would neglect the simple improv strategies that we’d already reviewed (like using specifics), and we’d wander into the land of nebulous references. He wouldn’t let it fly, though, and it was a relief when he side-coached us into using the tools we should have already been using to keep it on track.

This strategy in teaching helps immensely with developing the muscle memory we all need to be able to know what a good scene feels like. It is one thing to say it, it’s another to do it. The workshops had us performing so much that I think everyone left knowing what it felt like to be in a solid scene.

“Words come from your head. The connection comes from your being. It’s about connecting with your partner on an emotional level first, and then letting the dialogue come second.”

Oh to fill that silence. The people are here for a show, so let’s come out swinging! Right!?

Well, no. As clever as most improvisers are, it’s not entertaining to watch them dream up scenes and then try to communicate their ideas to their partner on stage live. That’s scripted comedy, and for that to be successful, there must be drafts, revisions, and rehearsals. This is improv, where we make it up. And improv is rooted in the unknown, the discovery, and the unexpected. As soon as we get into our head and try to plan the action, we lose the value of the improv.

In Jimmy’s class, we did a great exercise with no words. Our dialogue was only allowed to be numbers. We were given a tense situation – confronting a spouse, asking a child for money – to give the scene an emotional charge, and then we just alternated numbers 1 to 50. This was an amazing exercise to see how quickly the connection can occur between two players. Within seconds, they’re on the same page about how the scene is moving and the energy. Specific words aren’t needed to convey love, fury, disappointment, all we need is the energy.

Honestly, I believe this exercise would make for a great stage performance with a real audience as it is riveting to watch. But as soon as we can take this power and use real words with it, we are creating not just another scene but a compelling exploration of life and people. That’s gold, and that’s what improv is about. The laughs will come or they won’t, but the scene will be good and your audience will love you.

“… you have a choice: you can strive to create something that is more like theater, that may move people emotionally, or you can strive to create something that is more like bad stand-up, that hopefully people will forget.”

I completed the 2-day workshop with Jimmy. After the first 4-hour session on Saturday, I left our space feeling emotionally drained and physically exhausted. My brain was rattling with an endless stream of ideas. I was able to look at my own style and see that I was avoiding my shortcomings, to the deficit of myself and my colleagues. It was humbling.

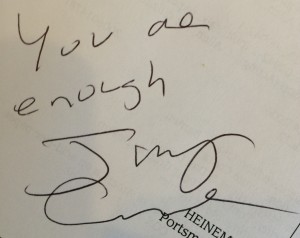

In all honesty, I absolutely did not want to return for the second day. The amount of exposure that Jimmy subjected us to was unnerving, and although I loved my fellow performers in the workshop, it was difficult to lay it all on the line. Saturday night, I had a gut-wrenching feeling that I was not good enough, that I didn’t belong in the improv community. My confidence was shaken. Thankfully, I told my wife this, and as only a knowing spouse can respond, she stated flatly, “Isn’t that the point?” Touché.

When I returned Sunday, my confidence was still shaken. I still felt inadequate and I was scared to dive in. Throughout the class, I found more and more holes in my improv that I would have to address. But I also found confidence. One of Jimmy’s greatest qualities, in my opinion, is that he does not pretend that the road is easy. He acknowledges in himself and in everyone, star or otherwise, that the journey is rocky. No path is lined with gold. While natural talent exists, no great improviser can survive on that alone.

I hope that I have the opportunity to experience Jimmy again in my improv lifetime. Fortunately, if we don’t meet again, between his podcast, blog, and book, I’m confident I can continue to learn from him. (But I still hope he comes back.)

You can read more about Jimmy Carrane on his website http://jimmycarrane.com/. You can also purchase his book here:

http://jimmycarrane.com/shop/improvising-better-a-guide-for-the-working-improviser/